Or, to quote novelist Michele Roberts, “Rhys took one of the works of genius of the 19th Century and turned it inside-out to create one of the works of genius of the 20th Century”.Īs well as ensuring that the hellish fury in the attic became human, a harrowing figure rather than a fearful one, Rhys also gave us another, infinitely crueller Rochester. As author Danielle McLaughlin recently put it, writing for The Paris Review: “The novel didn’t just take inspiration from Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre, it illuminated and confronted it, challenged the narrative”. Something else has become clear, too: the novel has forever changed the way we read Jane Eyre.

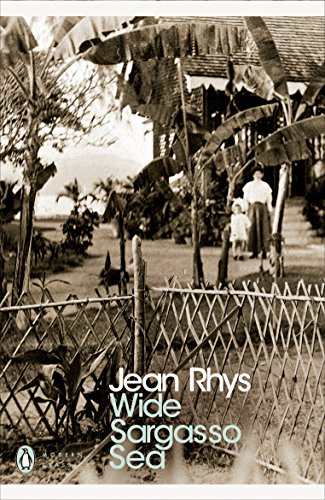

It sounds modest enough but half a century on, the book is enshrined in campuses around the world and beloved by readers of all stripes. “She seemed such a poor ghost, I thought I'd like to write her a life”, Rhys explained of her feelings for the first Mrs Rochester. It’s a novel that evokes a vivid sense of place, immersing the reader in the intoxicating lushness of its Caribbean setting it’s hard to put down and impossible to forget and of course it provides a potent heroine, plucked half-formed from the shadowy margins of one of literature’s best-loved romances, a woman whose tragic end comes to seem almost triumphant in light of all that precedes it. In giving a voice and an identity to Mr Rochester’s first wife, Antoinette – aka Bertha, the madwoman in the attic – the novel has become a gateway text to post-colonial and feminist theory.įor our insomniac listeners, this story of the couple’s meeting and ill-fated marriage, narrated in part by Antoinette, as yet a wealthy young Creole beauty, and in part by her domineering, cash-strapped new husband, Englishman Edward Rochester, offered more straightforward pleasures. One of these was a slender, quietly published novel that dared to take on a bulky 19th Century classic and is currently celebrating its 50th anniversary: Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea.Īs any English literature student will tell you, Rhys’s iconic prequel to Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre is rich in motifs and devices both modernist and postmodernist.

We had some regular callers, and we had a few titles that, whatever the show’s theme in any given month, would crop up again and again.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)